New rules allow joint diagnosis of autism, attention deficit

About 30 percent of children with autism have symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, but under current diagnostic guidelines they can only be diagnosed with one or the other. That’s about to change.

About 30 percent of children with autism have symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but under current diagnostic guidelines they can only be diagnosed with one or the other1. That’s about to change.

The next version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which lays out guidelines for diagnosing psychiatric disorders, is expected in May 2013. The DSM-5, as it is called, eliminates a troublesome passage in the current version that has prevented doctors and researchers from describing ADHD and autism as disorders that can occur together.

“It has been kind of silly,” says Bryan King, a member of the working group charged with revising the guidelines for autism. “Everyone identified these behaviors as common and significant in autism, but we were unable to call them out formally as ADHD.”

The changes to the guidelines are long overdue. Within a few years of the DSM-IV’s debut in 1994, researchers began suggesting that the exclusionary rule doesn’t make sense, says King.

For example, he says, “clinical trials had to do some interesting contortions,” such as calling the symptoms of hyperactivity and attention deficit in autism “ADHD-like.”

One of the reasons for this separation was fear that autism would be under-diagnosed, says James Harris, director of developmental neuropsychiatry at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, who is also a member of the working group.

Harris says framers of the DSM-IV believed autism-related inattentiveness could be confused with ADHD, and children who could benefit from autism therapies might not receive treatment.

“Many kids with autism do have attention issues,” he says. However, the nature of the problem is different than in ADHD. It’s difficult to get the attention of children with ADHD or to keep them on task. In contrast, children with autism have trouble shifting attention away from their narrow range of interests.

Forcing clinicians to choose between autism and ADHD may have been helpful in some ways — for example, requiring them to scrutinize subtle behaviors more carefully, says King, who is director of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Washington. But it is likely to have also had an adverse effect on children who have both disorders, preventing them from receiving proper treatment.

Outdated lingo:

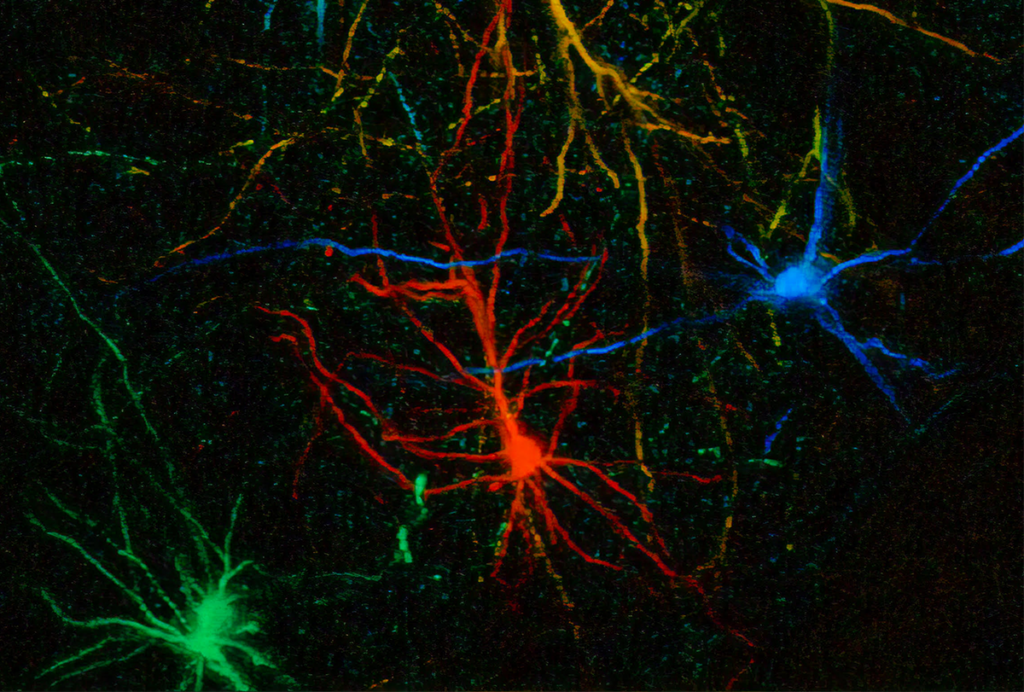

Research published over the past decade has provided growing evidence for the overlap between autism and ADHD. Genetic studies suggest the two disorders share genetic risk factors, and epidemiological studies confirm that some people with autism have symptoms of ADHD, and vice versa2. Neuroimaging and anatomical studies have also shown similarities between the two disorders.

Under the DSM-5 guidelines, doctors can directly analyze whether children with a primary diagnosis of ADHD and some autism symptoms might benefit from strategies designed for autism — such as social, speech and occupational therapies.

Likewise, children diagnosed with autism who show symptoms of hyperactivity, inattentiveness or impulsivity may benefit from treatments designed for ADHD3.

Treating these children with low doses of stimulants, such as Ritalin, often helps them to sit through classes without being disruptive, and may make speech or social therapies for their autism symptoms more effective, says Harris.

Doctors already prescribe these drugs for children with autism. But because of the language in the DSM-IV, the prescriptions are off-label and the doctors must say they are treating ”ADHD-like” symptoms rather than ADHD itself.

Acknowledging that the two disorders co-occur might also benefit clinical studies. For example, it’s possible that children who have symptoms of both autism and ADHD represent a unique subgroup. If that is the case, studying this group may help researchers identify risk factors or treatments specific to them.

“Once you have the ability to more effectively capture the population with autism and ADHD, that may become very useful for future genetic studies,” says King.

Other proposed revisions to autism in the DSM-5 have sparked controversy. Ruling out Rett syndrome, collapsing some disorders — such as Asperger syndrome and pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified — into a single diagnosis, and narrowing autism’s core characteristics from three to two, have all inspired criticism.

But removing the restriction on a dual diagnosis of autism and ADHD appears to be universally endorsed. “This announcement has generated applause at Autism Society meetings, which is pretty extraordinary,” says King. (The Autism Society is an advocacy group based in Bethesda, Maryland.)

The American Psychiatric Association, which publishes the DSM, says experts will review the proposed guidelines this fall and then present them in December to the organization’s board of trustees.

References:

Recommended reading

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Autism traits, mental health conditions interact in sex-dependent ways in early development

Explore more from The Transmitter

To make a meaningful contribution to neuroscience, fMRI must break out of its silo