Eye-tracking brings focus to ‘theory of mind’

People with Asperger syndrome don’t automatically show ‘theory of mind’, the ability to understand the desires and beliefs of others, according to a report published 16 July in Science. Instead, they seem to use deliberate reasoning to understand social behaviors, learned after years of practice in the real world.

Watch the video

People with Asperger syndrome exhibit a mix of social abilities that has long puzzled researchers. For example, when read a hypothetical story with key clues, they can accurately predict a character’s thoughts. Yet they may have trouble engaging in interactions with others that are complicated by gestures, deception or irony.

The reason for these contradictory responses is that people with Asperger syndrome don’t automatically show ‘theory of mind’, the ability to understand the desires and beliefs of others, according to a report published 16 July in Science1. Instead, they seem to use deliberate reasoning to understand social behaviors, learned after years of practice in the real world.

“The fact that some autistic individuals can pass theory of mind tests reflects the entire problem of treating these individuals — they can do a specific behavior if taught, but they will have difficulty in the next real-world situation,” says Ami Klin, director of the autism program at the Yale Child Study Center, who was not involved in the new work.

Asperger syndrome is on the autism spectrum. People with Asperger syndrome usually exhibit autism’s characteristic repetitive or restrictive patterns of thought and behavior but, unlike people with other forms of the disorder, they usually have higher intelligence quotients (IQs) and retain early language skills.

Many older studies had found that, unlike most people with autism, people with Asperger syndrome score well on theory of mind tests2,3. Some scientists had proposed that the higher IQs and verbal abilities of people with Asperger syndrome allow them to learn these skills, but the new study is the first to give direct evidence for that idea.

“This was the missing piece of the puzzle — to show that the intuitive, spontaneous bit of theory of mind is the piece that doesn’t seem to work,” says lead investigator Uta Frith, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London.

Sally and Ann:

Theory of mind was first studied in people with autism in 1985 by Frith and her graduate student Simon Baron-Cohen, now the director of the Autism Research Centre at Cambridge University.

Together with Alan Leslie, now director of the Cognitive Development Laboratory at Rutgers University, the team developed what became the standard method for evaluating theory of mind: the ‘Sally-Ann false-belief task’4. Researchers tell young participants a story, beginning with Sally and Ann looking at a marble in a basket. Sally leaves the room, and Ann moves the marble to a box. Researchers then ask the participant to deduce where Sally will look for the marble upon her return. Participants showing theory of mind predict that Sally will act on her false belief, looking in vain for the marble in the basket.

When scientists first administered the test in the mid-1980s, they usually told the story out loud. People with autism cannot pass this version, whereas healthy 4-year-olds can.

Theory of mind was meant to describe the inability of a person with autism to interpret the thoughts and motivations of others. Soon after the term’s coinage, researchers believed the absence of theory of mind might explain what is wrong with the brains of people with autism, and that it could be measured with the false-belief test, says Rebecca Saxe, a cognitive neuroscientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

That was largely disproven, however, when follow-up studies found that people with autism and good verbal skills can pass cartoon or verbal versions of the false-belief task — despite the fact that they are confused by real social interactions2,3.

“Theory of mind could no longer be the sole explanation [for autism] when the laboratory measure no longer gave individuals trouble, but the real world still did,” Saxe says.

To get to the root of these discrepancies, researchers turned to the question of when — and how — theory of mind develops in healthy children.

Eye tracking:

Over the past decade, researchers — typically using verbal tests — have argued that theory of mind develops around 3 to 4 years old5. But in 2005, scientists from McGill University investigated how 15-month-old healthy toddlers respond to videotaped Sally-Ann-type events. The team found that babies look longer at the revealed object when it appears in an unexpected spot6 — suggesting that even young toddlers have theory of mind.

Still, it wasn’t clear whether babies learn theory of mind, or apply it spontaneously. To find out, in 2007 Atsushi Senju, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of London, used eye-tracking technology to measure where healthy 25-month-olds look when watching an actor and a puppet play out a Sally-Ann scenario. With the actor turned away, the toddlers watch the puppet move a ball from one box to another. When the actor turns around, Senju found that toddlers immediately look to the empty box that the actor believes still holds the ball — suggesting that the toddlers have a spontaneous theory of mind7.

Because eye movements happen quickly and automatically, a participant can ostensibly take this version of the false-belief test without consciously thinking about it — making it a befitting paradigm for studying theory of mind in people with Asperger syndrome.

In the new study, Senju and Frith showed the same puppet show to adults with Asperger syndrome. Unlike healthy controls — who glanced first where the actor was expecting the ball to be — participants with Asperger syndrome looked about equally at the two boxes. This was particularly surprising because a separate experiment confirmed that the same participants with Asperger syndrome can pass a verbal version of the task.

The results show that people with Asperger syndrome seem to compute theory of mind differently than do healthy people — even young children, says Senju.

Cognitive models:

The new study is part of a larger push toward measuring how people with autism behave in the real world. “The real social world comes fast and furious, and with no instructions,” says Saxe.

To that end, she plans to combine eye-tracking and brain-imaging technologies to probe theory of mind in real time.

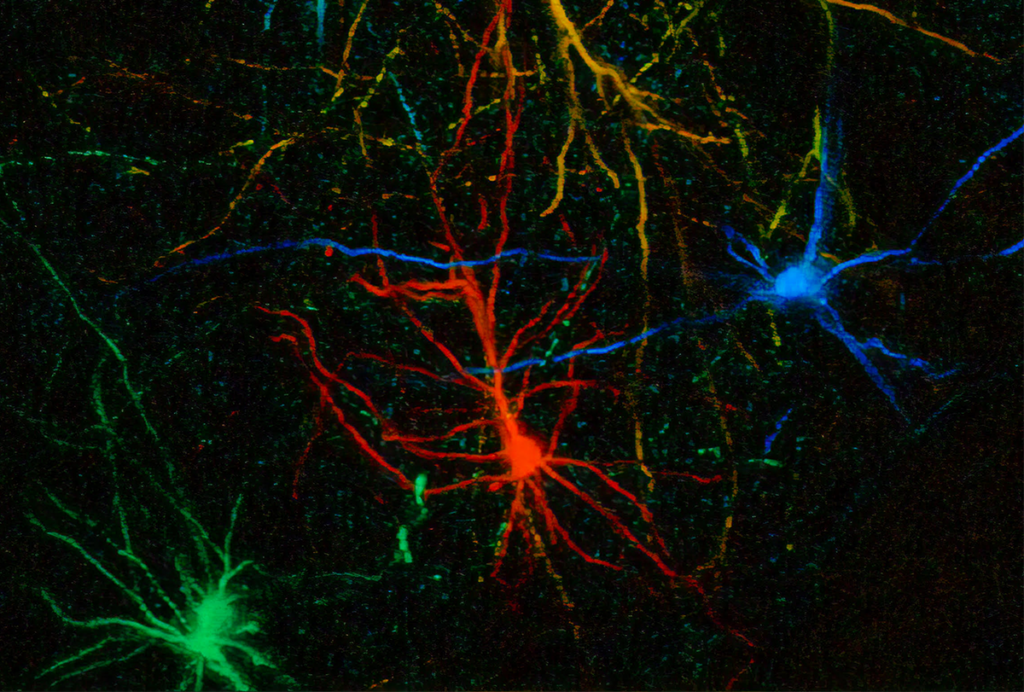

In 2003, Saxe discovered a small brain region ― the temporoparietal junction ― that processes interpretations of others’ actions8. She now plans to show children and adults, with and without autism, live video of social interactions similar to those in the Sally-Ann stories. The experiments will determine whether healthy children and adults use the same brain regions to solve false-belief tasks as those with autism do, she says.

“We want to find that extra ingredient that helps one pass the false-belief test,” she says, adding that she hopes to further test whether and how that “ingredient” is related to spontaneity.

Others are using eye-tracking technology to look beyond traditional developmental psychology questions — such as Sally-Ann tasks — to evaluate new models of cognition.

Klin argues that measuring the action in social interaction — such as how babies watch another person’s physical movement — is a more useful way to model genuine social behavior than by using arbitrary laboratory tasks with well-defined responses9.

“Our brains become monuments to reactions that worked in the evolutionary past — the successes in social adaptation,” Klin says. For instance, newly hatched chicks preferentially pay attention to the movement of living creatures over that of inanimate objects. In that sense, he wonders whether ‘theory of mind’ might more aptly be called ‘theory of body’.

Those social adaptations seem to be impaired in people with autism, however. In March, Klin reported that when shown moving dots of light, children with autism pay more attention to instances when big movements and loud sounds are synchronized than to ‘biological motion’, such as when the dots mimic a human walking10.

Using eye-tracking to further probe how information is processed in the brains of individuals with autism — and whether the responses to different false-belief tasks are learned or intuitive — will help determine which of these models of cognition is most accurate, Klin says. “Technology has an important role to play.”

References:

- Senju A. et al. Science Epub ahead of print (2009) PubMed

- Happé F.G. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 24, 129-154 (1994) PubMed

- Wellman H.M. et al. Autism 6, 343-363 (2002) PubMed

- Baron-Cohen S. et al. Cognition 21, 37-46 (1985) PubMed

- Ritblatt S.N. J. Genet. Psychol. 161, 53-64 (2000) PubMed

- Onishi K.H. and Baillargeon R. Science 308, 255-258 (2005) PubMed

- Southgate V. et al. Psychol. Sci. 18, 587-592 (2007) PubMed

- Saxe R. and Kanwisher N. Neuroimage 19, 1835-1842 (2003) PubMed

- Klin A. et al. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 358, 345-360 (2003) PubMed

- Klin A. et al. Nature 459, 257-261 (2009) PubMed

Recommended reading

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Autism traits, mental health conditions interact in sex-dependent ways in early development

Explore more from The Transmitter

To make a meaningful contribution to neuroscience, fMRI must break out of its silo