Flair for faces forecasts future autism severity

Children with autism often have difficulty recognizing faces and interpreting emotional expressions. And those who struggle most with this tend to have more severe autism symptoms later on, suggests a new study.

Children with autism often have difficulty recognizing faces and interpreting emotional expressions. These skills are crucial for successful social interactions. That’s why the results of a new study are so intriguing: The children who struggle most with facial recognition tend to have more severe autism symptoms as teenagers.

The findings, published 28 January in Autism Research, suggest that problems with facial recognition in childhood predict autism severity. They also raise the intriguing possibility that impaired facial recognition contributes to the social deficits seen in autism. If this theory pans out, it may be possible to improve social skills in people with the disorder by giving them tools to better recognize faces.

The researchers measured the speed and accuracy of face and emotion recognition in 87 children with autism who ranged in age from 6 to 12 years. They used the ‘face recognition’ and ‘identification of facial emotions’ tests from the Amsterdam Neuropsychological Tasks — a battery of computer-based assessments of brain function.

They also measured autism symptom severity using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, a widely used diagnostic test, at the start of the study and again about seven years later, when the participants were teenagers.

During each test, a person’s face flashed on a computer screen for 2.5 seconds. In the face recognition task, the children saw an expressionless face and were then asked whether it appeared in a panel of four pictures. In the emotion recognition task, the children saw a face expressing one of four different emotions — happiness, sadness, anger or fear — and then had to say whether the face showed a particular emotion.

Lower accuracy on the face recognition test predicts more severe autism symptoms during adolescence, the study found. This holds true even after the researchers adjust for differences in symptom severity during childhood, ruling out the possibility that poor performance simply reflects autism severity. Accuracy on the emotion recognition task does not track with autism severity.

The findings fit with a popular theory that the intrinsic drive to seek out social experiences is impaired in people with autism, thwarting the development of certain social skills, such as facial recognition. This may hinder further social development and potentially worsen autism symptoms, the researchers speculate.

If the results hold up in future studies, they could have a variety of applications. For example, clinicians might one day be able to use scores on facial recognition tests to flag children at risk for severe autism symptoms and prioritize treatment. Facial recognition may also turn out to be an objective measure, or biomarker, that researchers could use when charting the efficacy of treatments for the disorder.

But first, of course, researchers must validate the tests and confirm that trouble with facial recognition can worsen autism symptoms — which is bound to be no small task.

Recommended reading

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

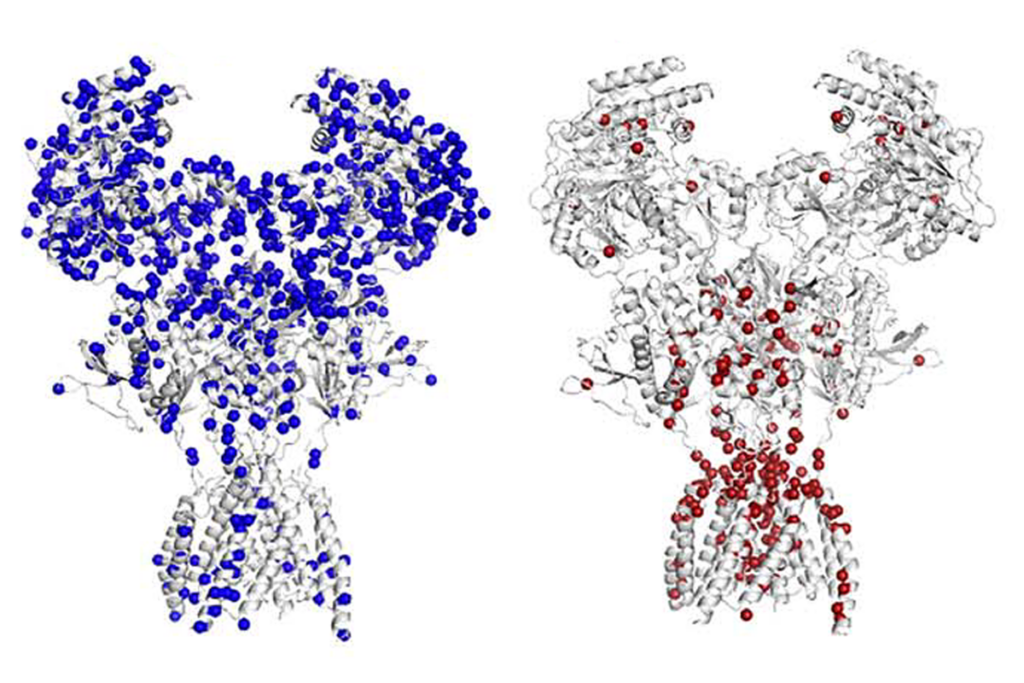

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Autism traits, mental health conditions interact in sex-dependent ways in early development

Explore more from The Transmitter

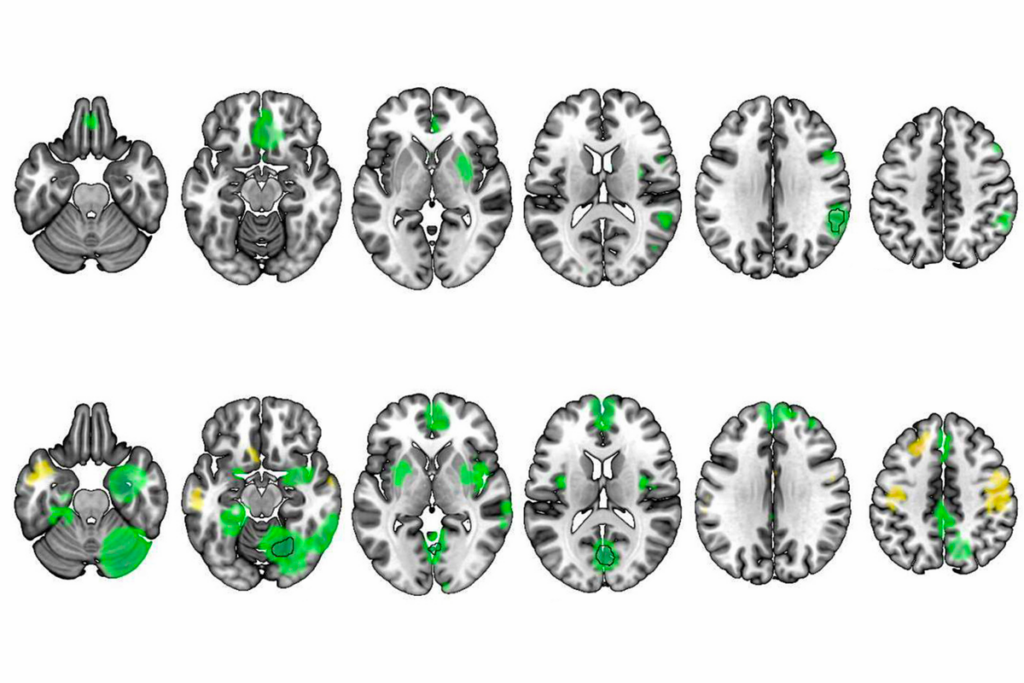

BCL11A-related intellectual developmental disorder; intervention dosage; gray-matter volume

Emotional dysregulation; NMDA receptor variation; frank autism