Brothers and sisters

People with autism have fewer children than average, and so do their brothers, according to a study of Swedes born between 1950 and 1970.

Scientists have puzzled over why autism continues to be a relatively common condition even though people with the disorder rarely marry and have children.

A study published 12 November in the Archives of General Psychiatry tackles this question by combing through Swedish population databases for information on about 2.3 million people born in that country between 1950 and 1970.

The researchers analyzed relative fecundity — how many children people with autism have compared with the general population, as well as how many children their siblings have.

Unsurprisingly, they found that people with autism have fewer children than average. Men with autism have one-fourth as many children as men in the general population, and women with autism about one-half as many as women in the general population.

One hypothesis for autism’s continuing prevalence is that some mutations are harmful when present in those with the disorder, but beneficial in unaffected relatives.

A beneficial mutation is one that increases a person’s evolutionary fitness, meaning the number of descendants he or she has. So, the researchers asked whether siblings might have more children than average and make up for the children that people with autism don’t have.

They found that brothers of people with autism also have fewer children than average, whereas sisters have slightly more.

The researchers also analyzed data from people with five other mental disorders — schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, anorexia nervosa or substance abuse — and their siblings.

They found that autism has a greater impact on childbearing than any of the other disorders. However, the researchers found similar patterns among people with schizophrenia and their siblings, an intriguing result given the shared genetic links between the two disorders.

New mutations, perhaps linked to older parental age, may play a strong role in keeping these disorders relatively common in the population, the researchers suggest. The two conditions may also represent examples of sexual antagonism, in which risk genes are harmful for males but beneficial for females.

This is all interesting, but it seems to me that the researchers’ emphasis on natural selection and evolutionary fitness leaves out how people actually make decisions about family size in the real world.

For example, siblings of people with autism may choose to have fewer children, or none at all, for fear of having a child of their own with the disorder. Or they may choose to have more children knowing that their affected sibling won’t.

Gender may affect these calculations, with brothers and sisters deciding differently. Nowadays, having or not having children is often a complex choice — and probably even more so for people who have family members with autism.

Recommended reading

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Explore more from The Transmitter

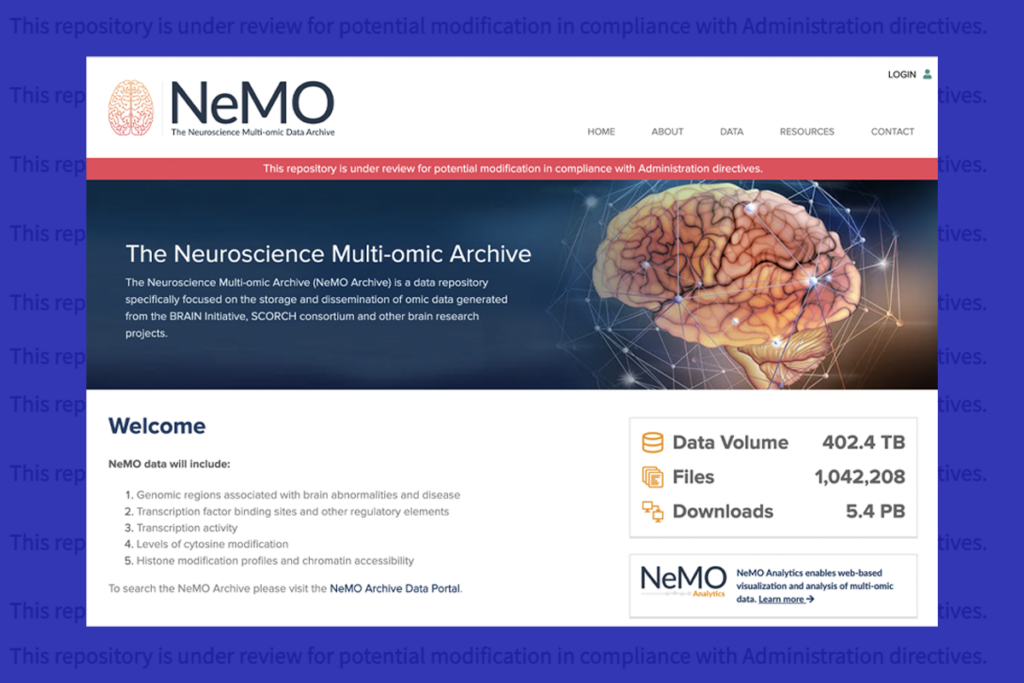

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors